Thursday, November 27, 2014

Thursday, November 20, 2014

a review of 'bad hair' by justin lockwood

It’s the truth the religious right never wanted to face: every gay adult begins life as a gay child. This reality is at the heart of Bad Hair (a.k.a. Pelo malo), a Venezuelan feature from director Mariana Rondón. It’s a small, slowly paced story about Junior (Samuel Lange Zambrano in a remarkable performance), a young boy with an overstressed single mom, Marta (Samantha Castillo), and a fixation on straightening his hair for his class photo. Marta's too distracted by trying to get her old job back to show Junior much affection, but this un-masculine preoccupation troubles her; Junior’s paternal grandmother Carmen (Nelly Ramos), meanwhile, is more accepting but wants to raise the child exclusively as her own. Junior, whose only friend is a fat girl with similar dreams of glamour, and who pines for the hunky teenager running the local newsstand, is caught in the middle.

Rondón portrays a sad look at life in Venezuela, with blocks of drab tenements and the children play acting murder and rape with dolls, without overstatement. The film is solidly made with great, naturalistic performances, and it builds gradually toward an unflinching conclusion. There are no easy answers here. Marta's not a bad mom, just a tired and overwhelmed one. Bad Hair is not a happy story, but it’s an important and truthful one.

-Justin Lockwood

Bad Hair is playing now at Film Forum

Follow me on Twitter: @HeyLockwood

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

Monday, November 17, 2014

Thursday, November 13, 2014

poetry reading

I will be reading poems Friday, November 14th at La Sala for the launch of the latest issue of No, Dear (guest edited by Morgan Parker).

Lineup includes:

Jeffery Berg (yours truly)

Joseph Bradshaw

Charity Coleman

Mel Elberg

Camonghne Felix

t’ai freedom ford

Renee Gladman

Jen Levitt

Melody Nixon

Liz Peters

Alexis Pope

Facebook event deets here.

LA SALA at Cantina Royal

Brooklyn, NY 11211

7 - 9 PM

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

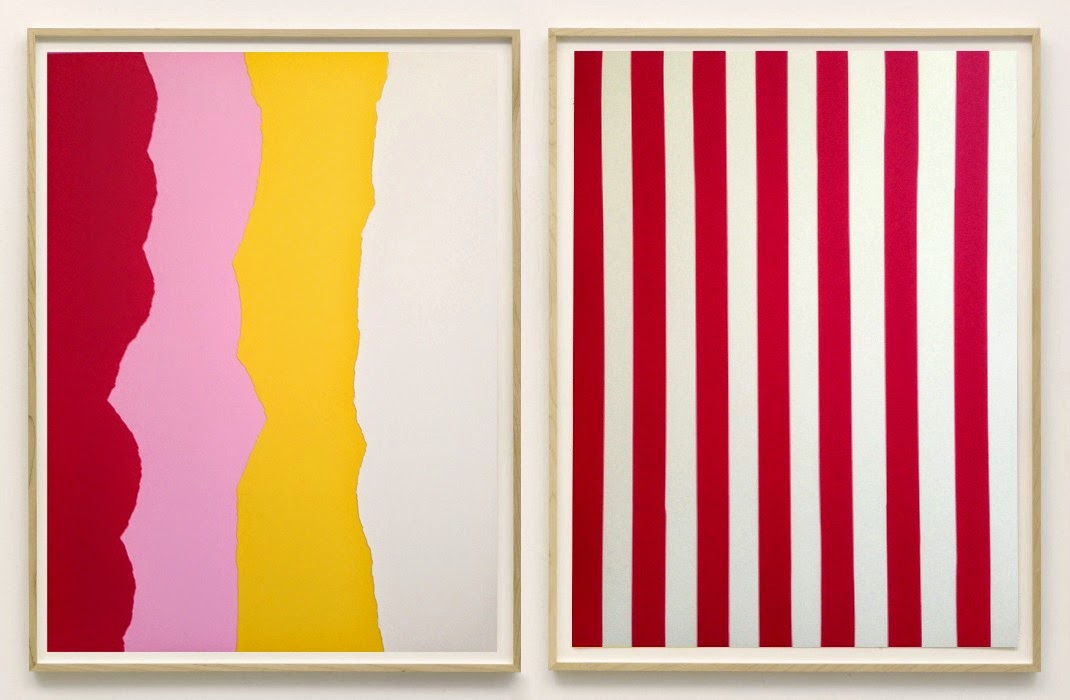

paintings by paige jiyoung moon

These are so delightful. Love all the details.

Cute Moonrise Kingdom one below.

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

Monday, November 10, 2014

blank space

Taylor hams it up and chops trees in the clip for "Blank Space." Shades of Last Year at Marienbad abound.

Director Joseph Kahn notes that “Taylor wanted to make a video addressing this concept of, if she has so many boys breaking up with her maybe the problem isn’t the boy, maybe the problem is her.”

cardboard collages by ibon mainar

I'm trying to channel these fun, bright pieces by Ibon Mainar on this sleepy Monday.

via Ibon Mainar

Saturday, November 8, 2014

christine: one cold-blooded hotrod by spencer blohm

If Carpenter hadn’t become involved, the film could have ended up just another failed 1980’s B horror film, forgotten by the masses and ironically celebrated by the aficionados of bad film. However, Stephen King and John Carpenter both shared certain artistic and societal ideas, and their sensibilities complemented each other well.

Christine is, superficially, the story of an alienated young man who comes into possession of a fifties Plymouth that has a mind of its own. What’s more, it has a penchant for murder. At its core, Christine is about the inanimate becoming animate, the idea and meaning of the soul, and the idea of an unstoppable enemy who is untouched by the methods one would usually rely upon to vanquish a foe.

Historically speaking, the concept of “the Other” has existed for quite a long time, but the first truly modern incarnation of this idea was in the silent masterpiece Metropolis. Directed by Fritz Lang in 1927 it was the first film to truly posit the idea of a creature that while not human, maintains a notion of humanity. It didn’t merely set a precedent for a film like Christine — it set the precedent for all contemporary film. Similar in fashion to the eponymous vehicle of Christine, the Robot, or as it is called in the film, “Maschinenmensch,” causes nothing but pain and sorrow for those associated with it and in the end is destroyed to protect not only the protagonists of the respective stories. While both the villains in each story are machine at their core, Metropolis’s antagonist is not known to be a robot, while the 1957 Plymouth Fury in Christine is obviously just that — a car imbibed with the angered spirit of a human being.

Yet another shared source of inspiration for Carpenter and King were the EC horror comics of the fifties — particularly the stories by Ray Bradbury. Christine is reminiscent of a Bradbury story that was used by EC entitled “The Coffin,” which deals with a killer coffin that has been engineered to seal itself and bury itself six feet under. Bradbury’s work commonly dealt with many themes that are recurrent in both Carpenter and King’s work: denigration of the environment, cultural insensitivities manifesting in horrendous ways, and, to tie it back in to Christine directly, autonomous technology. Bradbury was famous for saying that “People want me to predict the future. When all I want to do is prevent it. Better yet, build it.” This ethos seems to be simpatico with the personal philosophies of Carpenter and King. And where Bradbury’s eco-conscious The Martian Chronicles stories helped to create for a world where energy consumers are becoming more conscientious, Christine evidently failed to instill a deep enough fear of automated cars, as they’re currently being developed!

The future can look bleak in these films and novels of course, but these works do have one thing in common; the victory, or perceived victory as is the case with Christine, of the “true” humans. The Robot Maria is destroyed after the masses realize what they have wrought by following her, the vehicle in Christine is destroyed after the connection is made between suspicious deaths and the possessed car, and Bradbury’s automated house on Mars burns itself to the ground when it’s left to its own devices. The hope that human ingenuity and our connections to each other will always provide us the means to survive is the backbone of these stories — the technological aspects simply a modern day representation of “the Other.”

-Spencer Blohm

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)