Two new disco gems from Jungle!

Monday, May 30, 2022

Sunday, May 29, 2022

nitram

Going into the film Nitram by Justin Kurzel, known for bleak pictures like The Snowtown Murders and his muddy, overwrought adaptation of Macbeth, I wasn't aware of what it was truly about. The first half this Australian suburb-set tale almost felt like a loose, quirky Harold and Maude-type idiosyncratic love story with a shaggy blond intellectually disabled, heavily (and jaggedly) medicated late teen / early twenty-something titular character (Caleb Landry Jones) with a rowdy penchant for firecrackers and pushing boundaries, who has a pair of emotionally-stunted parents who just don't understand him (played by Judy Davis and Anthony LaPaglia), or perhaps, understand him too (frighteningly) well, and his unexpected relationship with an eccentric, sweet wealthy woman (Essie Davis) in her rambling mansion full of ambling dogs.

As it is not necessary to go into the film cold as I did, the film is based upon incidents leading up to the Port Arthur massacre, a 1996 shooting which took the lives of thirty-five people and wounding twenty-three others. Kurzel's film is essentially a close, detailed character study based upon the perpetrator. To take upon this story through this lens is definitely an audacious choice, and one, that could understandably make many upset, especially those close to the occurrence. There have been many movies and documentaries that take the point-of-view of real-life killers and the violent acts they have perpetuated. In some respect, one wonders why these films should be made. Nevertheless, Nitram, which reveals the real-life gunman as a child in the opening credits in a hospital, wounded by firecrackers, is cloudy: it doesn't feel exploitative nor stringently "tasteful."

Nitram is mostly captivating movie, much due to the specificity of its atmosphere--its houses, and cars and beachside landscapes, filmed with a quiet, almost unnerving distilled, golden quality (the cinematography is by Germain McMicking)--and, of course, its actors, who do incredible work through haunting subtlety (a transformative Landry Jones, Judy Davis, and a ghostly Essie Davis in particular). As the weary mother of Nitram, it is Judy Davis, with her lined face, tight, short haircut and banal clothing, who imbues inner grief and anger. Sometimes that inner grief and anger comes through when we see who she decides to look at and when, and also through the vicious antagonism she can dish out, occasionally under the veneer of genteelism. Midway through the film she tells a story of losing a young Nitram in a fabric shop--the way she reveals it is vivid and devastatingly taut; the story becomes almost fully symbolic of their whole overall relationship in general and also her son's psychology. Throughout, Kurzel demonstrates great sympathy towards these characters: it's mostly a film about behavior more than anything else. Although when the film moves towards Nitram's gallingly easy purchases of assault weapons, it veers into the polemic. The end title cards reveal Australian's ban and confiscation of weapons swiftly after the incident. While not every film in the world has to pertain to America, of course, this one hits hard after this past week, and the contrast of action versus inaction demonstrates just how irresponsible and feckless our political leaders have been for decades in the face of supporting a churning, reprehensible industry of greed over preventing mass murder. ***

-Jeffery Berg

Friday, May 27, 2022

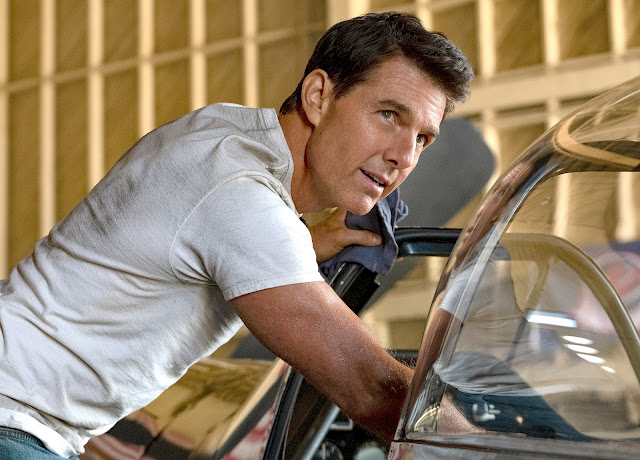

top gun: maverick

I remember being on the playground, and the boys I was with were naming each other: I'm Maverick. You be Goose. You be Ice Man. I didn't want to be any of these men. The original Top Gun was released around my sixth birthday in 1986 and I saw it with my father. I remember the Kenny Loggins track "Danger Zone" thundering, and back then, I mistook the lyrics as "I went to the candy store." The movie fits in my cinematic memories as hazy discomfort with my own gender. I knew I had to conform and play one of the male roles. How ever us boys ended up acting out flying separate fighter jets on the blacktop landscape of a South Carolina playground is unclear. The movie didn't speak to me then--its endless parade of machismo. I couldn't even begin to articulate my own queerness. Pauline Kael's review described Top Gun as a "shiny homoerotic commercial" with "pilots [strutting] around the locker room, towels hanging precariously from their waists." Years and years later, I would see this, of course, particularly in the slicked torso volleyball sequence backed with Kenny Loggins' steely rock rhumba "Playing With the Boys." In 1986, I couldn't process it, just as I didn't get the breezy sexual innuendo jokes of two other Paramount rental classics of my generation: Clue and Grease.

So I went to Top Gun: Maverick thirty-six years later with a queasy sense of unease. The trailer (played over and over again since 2019 due the film's logistic and COVID-related delays) suggested both the flagrant parading of unchecked patriotism and chiseled, gum-smacking crew cut masculinity that I don't connect with (and abhor). And yet, to my surprise, Joesph Kosinski's sequel is an electrifying experience. It is endlessly wistful about the past, as if pleading to the audience "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling"--The Righteous Brothers golden oldie that became a radio sensation again in the mid-to-late 80s again due to its use in the original film--and you want that lovin' feeling back.

Recommended by his old flying frenemy "Ice Man" (Val Kilmer), Navy test pilot Tom Cruise's Pete "Maverick" Mitchell is assigned to train a group of pilots on a perilous mission; one of the flyers is Maverick's late friend Goose's son, "Rooster" Bradshaw (Miles Teller), who hauntingly looks like him and even knocks off Jerry Lee Lewis' "Great Balls of Fire" on the piano. Maverick's unconventional training and bravado is met with stuffy disdain by Jon Hamm's Admiral. It's all very conventional movie plot mechanics. Though Cruise and the supporting players' disarmingly charming turns, make it pleasurable. There is just enough of lightly-sketched character development to cement a sense of pathos and believability. The underwhelming link is Jennifer Connelly's "don't break her heart again" love interest Penny. The sweeping violet blue-tinted passionate scenes set to Berlin's soaring "Take My Breath Away" of Cruise and Kelly McGillis (a great actor sadly not in the picture; though its probably accurate that her character has, too, moved on) is now replaced with a more matured picture of ordinariness in a generic upstairs bedroom with dusky blue pillows. Part of the issue could be the writing: Penny just doesn't have much of a personality, besides being the smiling, occasionally sly bartender.

Besides some thrilling drills, what ends up being tremendous in Top Gun: Maverick is its unbelievably well-shot (the photography is by Claudio Miranda), edited (the editing is by Eddie Hamilton) and executed climax and coda. Just on the edge of feeling ponderous, the mission is laid out to us in detailed ways (even though the enemy's origin is hidden): we get the stakes, the computer simulations, the timings, all of it. When we get there, it's momentous--both the suspense and the awe-inspiring visuals. I can't think of a mainstream action movie in years that has felt so rousing. Is it because there's a numbness and distance to all the bombastic, stake-less swirling CGI hodgepodge messes of prolonged fighting and dashing and jumping around explosions that have riddled Hollywood products for decades? The visual effects are difficult to even comprehend in Top Gun: Maverick because the real flying stunts are so visceral. In that respect, the sequel definitely is an exciting achievement, even if the plot and characters are somewhat route and the 80s hyper-masculinity and militaristic nationalism still lingers. But I returned from this film undeniably buoyed. Lady Gaga's "Hold My Hand" is a cliche love song, though her voice is towering. But as Harold Faltermeyer's stirring "Top Gun Anthem" blares effectively, it's not only a flourish of nostalgia but a reminder that action film scores (electronic or symphonic) used to have distinctive pop melodies that enhanced their movie's emotional currency. ***1/2

-Jeffery Berg

Monday, May 23, 2022

the innocents

Saturday, May 21, 2022

the same

men

Alex Garland's films (Ex Machina, Annihilation) and scripts (28 Days Later...) are usually effective at painting a splotchy universe of the cryptic follies of humankind and technology. Sometimes, like the film adaptation of his novel The Beach as well, the films of Garland take a sweeping swerve in their second half to something more harshly toned and obliterating. His Men follows Harper (Jessie Buckley) as she escapes alone to a cottage in the English countryside in the wake of tragedy. What's to come seems under the influence of a hazy hybrid of Robert Altman's Images and Polanski's Repulsion, with Harper perturbed by the awkwardly chummy estate keeper (Rory Kinnear playing his chewy role(s) with pizzazz) and encountering strange creeps out in the verdant wilds. The film moves slowly into an abrupt finale of garish horror, with pretty good gore effects, that as in The Howling, a character can only seem to stare and gawk at. Many have written about Garland's overt symbolism (yes, Harper munches on an apple as soon as she gets out of a car and sets foot on the estate's yard) and overt stab at "toxic masculinity." Yet, any sense of the politic, doused in a mix of religious gobbledygook, doesn't come through in an effective way. I left with a weird sense that the film was depicting Harper as unfeeling of mental illness and one deserving to be punished and tormented for her guilt; none of this seems like the message Garland was so hammering in trying to convey. Sometimes films like this linger in the mind, and welcome re-investigation, but the movie doesn't feel vigorous enough to want to return to. So the overall effort ends up muddled and a bit flat, despite some moody moments. I was particularly enraptured by Harper roaming the cozy house and traipsing the tranquil, green countryside; the hallmark scene for me is Harper amused at the echo of her voice in an abandoned train tunnel (the sound design and Rob Hardy's cinematography helps). Buckley is best in these quieter moments. Is that sense of comfort, wanderlust, and isolation deceiving? Is it only effective on certain people like loners and introverts? Men is praiseworthy for those careful creations of atmosphere, less so for its attempt at commentary, paranoia and horror. **1/2

-Jeffery Berg

Thursday, May 19, 2022

in front of your face

If I can think immediately of what has been in front of my face (and people on the city streets and trains) for many hours in this era, it would be... screens. That's why the title of Hong Sang-soo's latest film, the cinematic equivalent of a "short story" or a fleeting novella, is slyly humorous, especially in these screen-ridden times. What can be marvelous about Sang-soo's work is how stripped-down and modest the films are--long scenes of chit-chat, social awkwardness, and simmered-down tension that often barely rises to a boiling point. This is the exact opposite of a lot of current American film and, especially, popular episodic television--where amplified conflict thwacks through every scene. This is especially a testament to Sang-soo's direction and writing--that his scenes can remain so introspective and compelling, even when nothing much (and yet so much) is happening. The structure of In Front of Your Face is well-drawn too--a morning into a morning after--a satisfyingly cyclical feel, with a haunting musical composition by Sang-soo bookending the piece.

A former actress, Sangok (Lee Hye-young), returns to Seoul from America and stays with her sister Jeongok (Cho Yunhee) in a sleepy, bland high-rise condo. We learn more about Sangok and her past as she breakfasts and takes a walk with her sister. Later Sangok returns to her childhood home, visibly moved, and stunned by how "small" the garden she used to play in now appears. And then she engages in a maundering dinner with a film director (Kwon Haehyo). It's there, in this space of a table, scattered with bottles and food, that a monumental secret is revealed. It feels like a leaden weight suddenly thrown into a delicately constructed tale that it almost feels humorous. But the philosophical musings Sangok utters (and also thinks about internally) are graceful muddles of regret, pain, and joy. Later, the reaction of keeled-over laughter at what could have been a devastating voicemail is one of the crowning moments in the movie. Hye-young, thin and often cloaked in her beige Burberry trench, is visually captivating amongst the city spaces (in stores and shops that are in times of after-hours) and landscapes and the occasionally vibrant green gardens and natural backdrops that emerge. She slips through the picture, sometimes with a cigarette, like the lost, faded star her character is or perhaps, imagines herself to be. ***

-Jeffery Berg

Wednesday, May 18, 2022

petite maman

After the ravishing Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Céline Sciamma hones in on an equally intimate, but less visually flashy tale in the quiet and exquisite Petite Maman. It harkens back to Sciamma's excellent Tomboy, which carefully and sensitively examined the perspective of a child. Petite Maman is almost like a fable, a film that could be played in any year as allegorical to one's own life, its power perhaps residing in how one is able to respond to its quaintness.

After the death of her mother, a young woman (referred in the credits as simply La mère, played by Nina Meurisse) cleans out her childhood home with her partner (Le père, played by Stéphane Varupenne) with her loving, inquisitive daughter Nelly (Joséphine Sanz) in tow. Curious about her mother's childhood, and grieving quietly for her grandmother, Nelly goes to the woods where her mother used to play. There she falls into a parallel existence, meeting Marion (Gabrielle Sanz) who ends up being an eight-year old version of Nelly's own mother. One can imagine the magical realism of films like The Enchanted Cottage or even Back to the Future. Robert Zemeckis' film is a flashy, comical sci-fi quest into wistfully altering the fate of a white middle-class America family; the movie is soaked with wall-to-wall music and consumerism of the 1950s and the 1980s.

Sciamma's film does not particularly have strong markers of any particular era. Even a hidden patch of "dated" wallpaper could be from the 70s, 80s, or 90s or even an attempt at a sort of vintage chic in the 2000s. The film also thrives not on music or bombast, but on the minutiae of tiny sounds of interactions of things with the body--eating crunchy snacks, drinking milk out of chocolate cereal, spreading shaving cream on the face with a brush, the rustling of sheets on a couch. These smacks and wisps of sounds pepper the film with a seemingly acute purpose of portraying closeness--almost ghostliness--the traces of sounds we leave behind when we interact with the physical world. When music suddenly hits the film, it does so broadly, with a child's perspective of an island pyramid given a particularly dreamy heightened power. The music is almost like a simultaneously satisfying and queasy sugar rush after a long bout of going without carbs. Sciamma's 72-minute film often feels egg shell-fragile, as if it's constantly tip-toeing around in quietness--resisting pushing the viewer's emotions in any particular direction. It's also gently playful and assured. An inside-out sweater made right-side-out and an edit of "transporting to tomorrow" may symbolize the "passing over" to a new plane; shaven faces and put-upon costumes suggest the trickeries of age and identity. Claire Mathon, whose cinematography recently showed prowess with the fuzzed memories of the past in Spencer--particularly when Diana physically and psychologically crawled into the ruins of her childhood home--lenses Petite Maman deftly. The atmosphere of hushed houses at night (shadows playing on the floor like a "black panther") and in the afternoon light, and the damp, leafy autumnal forest where Nelly and Marion play are all striking visual worlds to linger in. ***

-Jeffery Berg

Thursday, May 12, 2022

art by alai ganuza

Sunday, May 8, 2022

the heart part 5

Kendrick Lamar's video for "The Heart Part 5."

An artist that's always reflective and moving things forward.

Directed by Dave Free & Kendrick Lamar

Deep Fake: DEEP VOODOO

Director of Photography: Christopher Ripley