Monday, December 1, 2014

on 'gone girl' by rishiv khattar

David Fincher’s Gone Girl begins and ends with the same image of a girl’s head. In both cases there is a male voiceover proclaiming how difficult it is to understand the complex workings of this girl’s (every girl’s) mind. But the film in between those images isn’t interested in understanding that mind.

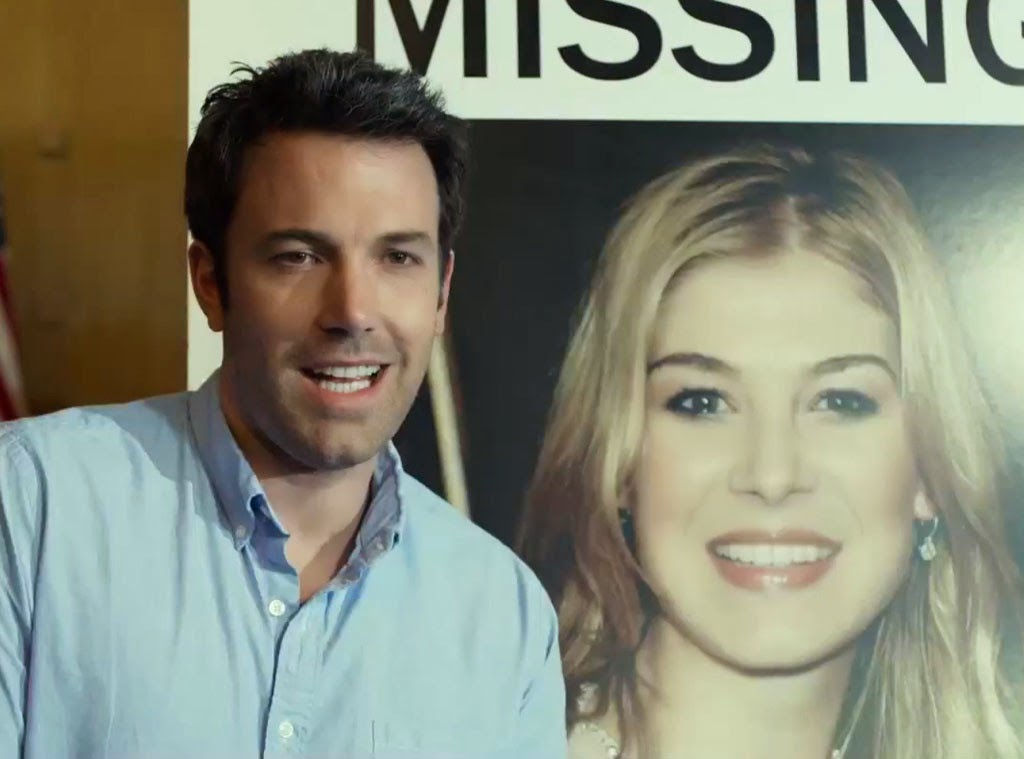

Gone Girl is less concerned with the images it trafficks in: Nick Dunne’s goofy vacant gaze (teased out through the film as either a sign of Nick’s guilt or Mr. Affleck’s inability to express his character) upon his wife Amy’s inscrutable face; than in building a case for a broad indictment, both silly and ambitious, of the institution of marriage.

If the film were more conscious of its casual misogynist imagery and reluctance to explore Amy’s motivations, it may not have so undermined its argument that marriage equally victimizes and entraps both its participants. Instead, the only insight this film delivers is that its central character, Amy (a chilly and severe Rosamund Pike that makes Ben Affleck’s blank emotional register appear friendly and expressive by comparison), is a sociopathic seductress not to be trusted or known. If this marriage is an archetype of all marriages and dynamics between the sexes, as the film intends, then this woman is typical of all women. Why strive for a nuanced understanding when, in the words of Nick’s twin sister (Carrie Coon): “everyone knows complicated is short for bitch?”

Sure, there is fun to be had in watching Amy’s character in the mold of a juicy femme fatale and in the wild turns of the plot from romance to revenge flick to gothic horror. But it is the basest of entertainments given a lofty guise by Fincher’s detached and icy compositions. This detachment perhaps explains the film’s reception. It allows for every fight between Nick and Amy to reverberate beyond its specifics to the relations between the sexes, for every plot deception to stand for the universal hiding and fakery in every marriage. It also allows the film to conveniently play as both a satire and a grave thriller; to masquerade trashy stereotypes about both women and men as symbolism and insights. When Nick tells Amy that all they did was “resent each other and cause each other pain,” she responds: “that’s marriage.” The messaging here is that the insane behavior of the characters on screen is holding a twisted mirror to some inherent truth in all marriages.

With the right detachment, it’s easy to say that’s both inane and reductive and also easy to call it somewhat profound. There’s a parallel for our entertainment (the film is intensely watchable despite its problematic themes and characterizations) in the puerile and voyeuristic media watching and picking apart Nick and Amy’s marriage. Fincher spends a lot of time on these scenes both parodying talk show hosts and adding their views to the multiple perspectives in the film: Nick’s narrative, Amy’s narrative, Amy’s diary, the police’s narrative, Amy’s parent’s opinion. The film posits that people are essentially unknowable and their guilt or innocence and the success of their relationships are socially determined by these many eyes. It’s unfortunate then that the film’s trajectory only serves to confirm the most crass and simplistic of these perspectives.

-Rishiv Khattar

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment